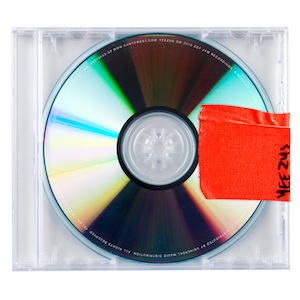

Available on: Roc-A-Fella / Def Jam

Just a minute into Yeezus, Kanye West lays his cards on the table, posing the rhetorical question “How much do I not give a fuck?” before breaking the song’s acidic spell and sampling a gospel choir: “He’ll give us what we need / It may not be what we want.” It’s a succinct mission statement for what will follow: 40 minutes of violent, sexual, heretical hip-hop that is built to confound and challenge listeners.

Yeezus is the culmination of the movement that began with 2008’s equally-divisive 808s and Heartbreaks. That album marked a shift in Kanye’s work from the radio-friendly hitmaking that defined his first three albums to something more experimental and ambitious, from that album’s bleak, Autotuned melancholia to the decadent grandiosity of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. Each album followed turmoil both internal (his mother’s untimely death, a broken engagement) and external (the Taylor Swift incident and ensuing controversy, being called a “jackass” by President Obama). Likewise, Yeezus follows Kanye’s forays into other creative avenues, like fashion and design, where he ran into new gatekeepers and detractors. “I can create more for this world, and I’ve hit the glass ceiling,” Kanye said in his revealing New York Times interview. “If I don’t scream, if I don’t say something, then no one’s going to say anything, you know?”

On Yeezus, Kanye screams plenty, both literally and figuratively. The threads of money, power, fame, and race have always been weaved through his lyrics; now they’re just more focused and intense. For Kanye, the personal is inextricably political, and he finds the new challenges he has faced endemic to society as a whole. Throughout the record, Kanye confronts and re-appropriates racist characterizations of the black man in America, notably the idea of black men on the prowl for white women. Rather than refute it, he embraces it, most vividly on ‘New Slaves’: “Fuck you and your Hampton house, I’ll fuck your Hampton spouse / Came on her Hampton blouse and in her Hampton mouth.” ‘New Slaves’ attacks everything from the casual racism of storekeepers to the systemic racism of drug policy and the US prison industry, and the evocatively-titled ‘Black Skinhead’ invokes Malcolm X’s “by any means necessary” proclamation. Kanye has always talked about race, but never before from a Black Power stance.

To deliver revolutionary ideas, Kanye required revolutionary music. Yeezus is sonically abrasive, blasted with distortion, feedback, and bowel-rupturing bass and ragged with screams, chants, and gasps. The elastic, modular synths and percolating beats of ‘On Sight’ would be just as at home on a Nine Inch Nails record; the rumbling drums of ‘Black Skinhead’ were initially (if inaccurately) credited to Marilyn Manson’s ‘The Beautiful People’. There are elements of acid house and industrial and dancehall, often in the same song, and the songs frequently take unexpected turns, smash cutting into divergent styles. The sinister bassline and operatic synths of ‘New Slaves’ give way to a sweeping, Autotuned movement that suggests hope and imperfection. Forget all the talk of a “minimal” album: Yeezus is densely layered and reveals itself on multiple listens.

Yet not everything is new: Kanye and company’s crate-digging yields samples and interpolations both obscure (Hungarian prog rock, Bollywood soundtracks, long-lost Ohio soul) and familiar (‘Strange Fruit’, Tom Jones via Beenie Man), with nods to hip-hop both classic and contemporary (e.g. Lords of the Underground’s ‘Chief Rocka’ and Pusha T’s ‘Blocka’, both on ‘Guilt Trip’). Similarly, the Autotune of 808s that launched a thousand Drakes is a frequent counterpoint to the album’s industrial cacophony.

The album is relentless, reeling off a series of powerhouse compositions. On ‘I Am A God’, Kanye toys with the sacred-profane dichotomy, declaring himself both a god and a man of god, chatting with Jesus, and hinting at his goal for the album (“Soon as they like you make ’em unlike you / cos kissing people ass is so unlike you”). All the blaspheming doesn’t come without its price, as a breathless Kanye spends the final minute running from his demons over some melodramatic synths.

Kanye reunites with Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon and recruits controversial rapper Chief Keef for one of the album’s most powerful moments, ‘Hold My Liquor’. Amid riveting synths, arena-ready guitar lead, and heartbeat bass, Keef delivers the hook (“I can’t control my niggas / And my niggas they can’t control me”) with more hopeless resignation than a 17-year-old should be able to muster. Kanye clearly sees Keef as a kindred spirit: a Chicago rapper, chewed and digested by the media, and held up as a symbol (or cause) of everything wrong with society (in Keef’s case, Chicago’s wave of youth violence). There isn’t much room to reflect: ‘Hold My Liquor’ is followed by the drill-meets-dancehall sex anthem ‘I’m In It’. The halftime, pneumatic song is a pornographic checklist, with its most striking line (“Put my fist in her like the Civil Rights sign”) distilling the racial and sexual elements of Kanye’s worldview into one shocking image.

The lovelorn ‘Blood on the Leaves’ is the album’s centerpiece: a six-minute opus that borders on overwrought. The song interpolates C-Murder’s oft-referenced ‘Down 4 My Niggaz’, climaxes with TNGHT’s horns-and-percussion bombast, closes with an emotive, Autotuned gurgle, and, most notably, samples Nina Simone’s version of ‘Strange Fruit’. A touchstone of the civil rights movement, Kanye uses the painfully vivid imagery of the original to comment on relationships broken by drugs and fame. This isn’t Lil Wayne name-dropping Emmett Till; Kanye must be aware that he runs the risk of trivializing ‘Strange Fruit’. It might be a bridge too far, but it could be an attempt to insert himself into the timeline of civil rights discourse, on his own terms.

At ten songs and just 40 minutes, Yeezus is by far Kanye’s leanest album, yet it’s not entirely without its fat: the video game arpeggios and chopped Popcaan vocals of ‘Guilt Trip’ are interesting, but the song rings hollow (enlisting Kid Cudi doesn’t help, either). ‘Bound 2’ ends the album on a breezy note, but the sound collage — the Ponderosa Twins Plus One, Wee, Brenda Lee’s “uh huh, honey”s, Charlie Wilson’s livewire R&B hook — seems disjointed. Elsewhere, Kanye swings for the fences and hits some lyrical pop-ups: “Swaghili” is “Swagu,” part two.

Like this year’s most notable albums, much has been made of Kanye’s studio partners, but beyond recognizable vocalists or previously-revealed collaborators (e.g. TNGHT on ‘Blood on the Leaves’), trying to parse out who did what is basically impossible. Not to diminish the contributions of boldfaced names like Daft Punk and RZA, or underground talents like Evian Christ, Arca, and Gesaffelstein, but this is Kanye’s record: a cornucopia of concepts and collaborators reduced to a singular vision.

That vision is what makes Yeezus stand out as one of Kanye’s finest moments. Faced with making a career defining album, he opted for a palette of uncommercial sounds and ideas that takes his artistry to a level unparalleled in hip-hop (and pop music, for that matter). Kanye isn’t the first artist to fuse rap, politics, and industrial soundscapes, but because of the size of his megaphone and his position in the culture at large, he is perhaps the most important and subversive artist to do so. “I think that’s a responsibility that I have,” Kanye told the Times, “to push possibilities, to show people: This is the level that things could be at.” On ‘I’m In It’, he wants to “pop a wheelie on the Zeitgeist,” and on Yeezus, he succeeds.